Polityka prywatności

Zasady dostawy

Zasady reklamacji

Straightahead / Mainstream Jazz

premiera polska: 2021-01-22

kontynent: Ameryka Północna

kraj: USA

opakowanie: kartonowe etui

opis:

Editor's info:

On his third album, Joshua Redman joined forces with some of the most exciting younger players in jazz—each a virtuoso on his instrument, and each now a celebrated leader in his own right: pianist Brad Mehldau, bassist Christian McBride, and drummer Brian Blade. But don't expect youthful indiscretion here: as its name suggests, Moodswing is built on sophisticated grooves, along with a fresh, in-the-pocket band sound that would be a wonder at any age. And just what "moods" is this stellar quartet "swinging"? The song titles tell the story: the plaintive sound of "Sweet Sorrow"; the sly, easy swing of "Chill"; the stately grace of "Faith;" the playful bounce of "Mischief." But no matter the sound being explored, with these players, it's always the feeling that counts.

As Joshua himself put it, "Jazz is music. And great jazz, like all great music, attains its value not through intellectual complexity but through emotional expressivity. True, jazz is a particularly intricate, refined, and rigorous art form…. Yes, jazz is intelligent music. Nevertheless, extensive as they might seem, the intellectual aspects of jazz are ultimately only means to its emotional ends. Technique, theory, and analysis are not, and should never be considered ends in themselves."

LINER NOTES

Jazz is suffering today, but not in the way you might think. Contrary to the warnings of some professional (and amateur)) pessimists, jazz in the 90’s is alive and well. It is thriving, creative, inspired, provocative, and original. What jazz suffers from today is not artistic stagnation but popular mystification. Jazz, in other words, has a rotten public image – an image which was epitomized in a comment an acquaintance made to me just the other day:

“Jazz is cool and all, but it’s not really my type of thing. I mean, I respect it, but I can’t really get into it. I like music that makes me feel something. Jazz isn’t really about that. With jazz, you gotta think all the time. Jazz is all complicated and weird. It’s for those special types of people who like talking about stuff and figuring things out. Jazz is way too deep for me.”

This exact same view has been voiced innumerable times in countless different ways by jazz skeptics the world over. All jazz musicians are aware of it. Some ignore it. Some deny it. Some take great offense at it. Some have heard it expressed so often that they even begin to believe it themselves. But regardless of what specific forms this idea takes or what varying reactions it engenders, its central premise remains constant and abundantly clear: Jazz is an intellectual music.

According to popular notion, jazz is something which you research and study, inspect and dissect, scrutinize and analyze. Jazz twists your brain like an algebraic equation, but leaves your body lifeless and limp. In the eyes of the general public, jazz appears as an elite art form, reserved for a select group of sophisticated (and rather eccentric) intelligentsia who rendezvous in secret, underground haunts (or inaccessible ivory towers) to play obsolete records, debate absurd theories, smoke pipes, and read liner notes. Most people assume that the appreciation of jazz is a long, arduous, and painfully serious cerebral undertaking. Jazz might be good for you, but it just isn’t any fun.

This image is simple, powerful, and dangerously appealing.

But it is also egregiously false.

Jazz is music. And great jazz, like all great music, attains its value not through intellectual complexity but through emotional expressivity. True, jazz is a particularly intricate, refined, and rigorous art form. Jazz musicians must amass a vast body of idiomatic knowledge and cultivate an acute artistic imagination if they wish to become accomplished, creative improvisers. Moreover, a familiarity with jazz history and theory will undoubtedly enhance a listener’s appreciation of the actual aesthetics. Yes, jazz is intelligent music. Nevertheless, extensive as they might seem, the intellectual aspects of jazz are ultimately only means to its emotional ends. Technique, theory, and analysis are not, and should never be considered, ends in themselves.

Jazz is not about flat fives or sharp nines, or metric subdivisions, or substitute chord changes. Jazz is about feeling, communication, honesty, and soul. Jazz is not supposed to boggle the mind. Jazz is meant to enrich the spirit. Jazz can create jubilance. Jazz can induce melancholy. Jazz can energize. Jazz can soothe. Jazz can make you shake your head, clap your hands, and stomp your feet. Jazz can render you spellbound and hypnotized. Jazz can be soft or hard, heavy or light, cool or hot, bright or dark. Jazz is for your heart.

Jazz moves you.

If, then, the popular perception of jazz as an intellectual exercise is at odds with the reality of jazz as an emotional experience, what is to be done? How is jazz to be demystified? How can its image be revamped? These are problems which must be solved primarily by image-makers. Dedicated jazz musicians must concentrate first and foremost on their music. Still, when appropriate opportunities do arise, jazz musicians could greatly further the cause by de-mystifying peripheral theoretical jazz issues and instead directing attention toward the expressive core of their art.

That’s why, in writing about this recording, I’m going to refrain from technical discussions. I don’t want to talk about notes, phrases, chords, or meters. I won’t wax eloquently about melodic inversions, harmonic modulations, or polyrhythmic permutations. And I refuse to get bogged down in painfully-detailed, play-by-play, analyses of the various performances. (Besides, I have to leave something for other people to write about.) I actually have very little to say about this music, which I hope will speak clearly enough for itself.

I want just one thing to be known: Every composition on this recording exists to evoke a mood. Whether it be the hearty exuberance of “Rejoice,” the roguish playfulness of “Mischief,” the wistful reminiscence of “Past In The Present,” or the relaxed hipness of “Chill” – each song seeks to express a feeling, to conjure a spirit, to tell a moving, emotional story.

All these moods are, of course, general and open-ended. There is no single, ideal way to express the “Sweet Sorrow” of two lovers parting, or the “Oneness” of their reunion. There are no constant, definitive musical sounds which communicate the joyful anticipation you feel as you’re “Headin’ Home” after months on the road, or the crisp melancholy you experience waking up “Alone In The Morning,” or the “Faith” we all need to persevere through the dark periods of life. Similarly, none of these compositions possesses anything resembling a precise, literal meaning. No need to trouble youself wondering about the exact nature of my “Obsession,” or the specific subject of our “Dialogue.” Each composition intimates an endless number of potential meanings and permits an infinite variety of expressive interpretations.

Jazz is, after all, an improvised music. It demands sensitivity, spontaneity, and flexibility on the part of performers and listeners alike. The magic of the jazz experience lies in its irreplicability. Every sound is precious because it will never be played (or heard) in precisely the same way, at the same moment, in the same place, with the same feeling.

Thus it is best to think of these compositions not as exhaustive aesthetic dissertations but as loose tonal suggestions. Each song implies a basic mood. Each tune establishes an overall theme. After that it is up to us, as improvising musicians, to take these themes and weave them into personalized, inspired, spontaneous narratives. And it is up to you, as listeners, to take these moods and use them as windows to your own souls. Ultimately, these songs will be about your experiences, your impressions, and your emotions. They can mean whatever you want them to mean. They can be whatever you imagine them to be. They can take you wherever you wish to go.

So long as they make you feel.

—Joshua Redman April, 1994

popMATTERS

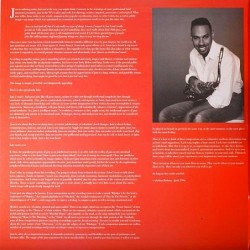

In 1994, Joshua Redman was the “It Musician” in jazz – a young guy getting a ton of press because he was a biracial guy who had gone to Harvard and decided to pass up Yale Law School for the life of a jazz musician. Plus, he was the son of the great tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman and took the top prize in the Thelonious Monk Saxophone Competition in 1991. Oh, and the guy could really play – boasting a rich, round tone on tenor and a natural, conversational style that was utterly appealing. All this resulted in a major recording contract, rare for almost any jazz musician, on Warner Bros. And the young player delivered with a debut that showed him as equally adept at “Body and Soul” and “I Feel Good”, then a sophomore effort where he played even-Steven with Pat Metheny, Charlie Haden, and Billy Higgins. The hype was not all hype.

For his third release, 1994’s Moodswing, Redman recorded with his working quartet. And it seems fair to guess that Warner Bros. decided to reissue this record because of that band. Pianist Brad Mehldau has become not only a top-flight jazz pianist but also a phenomenon of his own – a daring recording artist who tackles classical material and fascinating pop hybrids. Christian McBride has become jazz’s most prolific bassist, a man for all seasons and all styles. And Brian Blade has become not only the drummer in Wayne Shorter’s adventurous quartet but also an ingenious composer, arranger, and collaborator across musical styles. In retrospect, it is an all-star band, a supergroup. So how does Moodswing sound 18 years later? And how well does it fulfill its own mission, stated in Redman’s high-toned liner notes, to demystify jazz a bit, to rescue it from being seen only as an “intellectual music” and, instead, create feeling?

Well, it’s hard to say that this particular record, more than others of its ilk, communicates with truly unusual directness. This is mainstream jazz of the 1990s: post-bebop but also post-free jazz, jazz that has as its playground not only the whole history of the music but also popular forms from soul to rock and hip-hop. What Redman seems to have been doing here is something purer than any kind of “jazz crossover”, but maybe more substantive and valuable. He was working through several distinct jazz styles that have always satisfied, creating self-conscious variety. He was also making mainstream jazz that kept things concise and tasty – jazz with its swing and history intact, but a bit less fussy. Moodswing seeks to be that one jazz record you really want to play for your “non-jazz” friends.

The album begins with a smoky sense of melancholy on “Sweet Sorrow” – a slow, minor theme that allows Redman to show off his most vocalized tone. He bends the notes like a soul man, suggesting that part of Moodswing’s strategy for creating appeal is to let the saxophonist testify like a preacher – or a lover. The start of Redman’s improvisation comes on a series of notes that are bent far from pitch, after which he dives deep-down to begin the statement in his huskiest place. It’s a rich and compelling ride on a set of gorgeous blues phrases that are then curved around the larger harmonic structure. If the goal is to make the listener feel, then this is working.

“The Oneness of Two (In Three)” is an up-tempo jazz waltz that is, arguably, in the “My Favorite Things” bag – relatively simple chords changes that propel first Mehldau and then Redman’s tart soprano sax to thoughtfully ecstatic unfurlings. Blade, at least, is certainly operating in his Coltrane Quartet mode, splashing cymbals with delight like a lighter-handed Elvin Jones. This kind of cherry picking of previously successful styles continues with real precision on “Rejoice”. It’s a ripper, but not just a fast jazz tune. Instead, it calls on the kind of gospel-tinged groove that Keith Jarrett put into his quartet music back in the 1970s (of which Redman’s father was a key component) and then alternates it with energetic swing sections. Also, it is the longest tune on Moodswing, and it gives the soloists the chance to develop ideas within their improvised solos. This kind of thematic development is exactly what people ought to love about jazz, but it’s also the kind of taxing “thinking while listening” that Redman’s liner notes seem to be pointing away from. Whether that takes away from the leader’s garrulous tenor solo, with its section of over-blowing and soulful wailing, will probably depend on how big a jazz fan you are in the first place. “Faith” also cops a bit of the Jarrett gospel/jazz sound, but it starts as a gentle meditation and then develops a backbeat played on the rim of the snare as the theme is bandied about.

Without a doubt, Brad Mehldau is the secret ingredient on this disc. “Chill” finds a groove that lives somewhere in the Pink Panther/”Fever” zone: slinky and blue, set low in the tenor’s range, the bass and piano playing a lovely descending pattern. It’s a theme that isn’t, in and of itself, all that interesting, but it sets up the soloists just fine. Here is where the young Mehldau does his damage –playing light and easy, but with a melodic invention that is exceptional. It’s a solo that you might play for a skeptical friend who “doesn’t like jazz” and maybe win a convert. And when it’s Redman’s turn, things get interesting in a different way: the band sets of simple syncopated groove with no harmonic motion, and then the tenor and McBride’s bass trade blues rips. Nice.

Mehldau is also fascinating on the album’s clearest departure, “Dialogue”, which begins with a simple exchange of melodic lines but then becomes freely improvised. This track is surely not something that will make jazz more accessible to novices, but that doesn’t stop Mehldau from doing a majesterial job of creating a frame for what might otherwise be atonal exploration. From this track, his knottier future work winks at you.

In working through previous styles of jazz that struck a nerve with popular opinion, Redman does not ignore the bossa nova (“Alone in Morning”) or the jazz-funk groover (“Headin’ Home”). On the latter, McBride plays like a true groove machine with Blade hard on the backbeat throughout – not dumbed-down fusion, but a tough-minded take on the kind soul-funk that Blue Note produced in droves back in the 1960s. Mehldau colors it all with the hip rhythmic accents associated with Herbie Hancock’s funky playing. It is appealing, but not anything truly new or daring for a jazz quartet to pull off. And that is where any judgment of Moodswing probably has to land. It’s terrific music, but it is played over well-traveled territory. In jazz, that’s common and just fine, but it doesn’t really live up to Redman’s liner-note manifesto in emotional directness. As great as the band is, with a vintage that now spins our heads, in 1994, this was a young working band making its first recording. I’d call it lovely but not essential, incredibly fun but not ... moving. Not that it doesn’t make me feel something. Good jazz always does. If that’s not true for every music fan, I’m not inclined to lay it at the feet of a single saxophone player, particularly one with such range, tone, and ambition. Josh Redman was under no compunction to lead a movement. Moodswing shows how fine even a merely good date is by a strong player.

by WILL LAYMAN

muzycy:

Joshua Redman: tenor, alto, and soprano saxophones

Brad Mehldau: piano

Christian McBride: bass

Brian Blade:drums

utwory:

A1. Sweet Sorrow

A2. Chill

B1. Rejoice

B2. Faith

B3. Alone In the Morning

C1. Mischief

C2. Dialogue

C3. Oneness of Two

D1. Past In the Present

D2. Obsession

D3. Headin’ Home

total time - 01:09:39

wydano: 2021 (1992)

nagrano: March 8, 1994 - March 10, 1994, at Power Station, New York, NY

more info: www.wbjazz.com

more info2: www.joshuaredman.com

Opis