opis:

Editor's info:

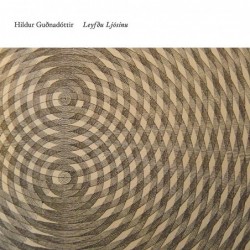

Hildur Gudnadottir's new album 'Leyfdu ljosinu' (Icelandic for 'Allow the light'), was recorded live at the Music Research Centre, University of York, in January 2012 by Tony Myatt, using a SoundField ST450 Ambisonic microphone and two Neumann U87 microphones. (NB - It was not played in a concert environment and there was no audience.)

To be faithful to time and space - elements vital to the movement of sound - this album was recorded entirely live, with no post-tampering of the recordings' own sense of occasion.

A multichannel version (Touch # TO:90USB) is also available - a 2GB USB stick in hand-made (by the artist) paper cover.You can read more about this here.

Reviews:

Brainwashed (USA):

On her third solo album (the title being Icelandic for "Allow the Light"), Hildur Gu?nadóttir presents a performance that is entirely live (without audience) of just cello, voice and electronics, which begins deceptively simple, but is soon molded into a rich work of intimate beauty as much as it is a complex study of the most rudimentary sounds in a compelling structure.

Consisting only of two pieces, the short "Prelude" is exactly that: a short, sparse opening of dry, unaffected cello playing that may have functioned as much as a warm-up for Hildur as it does for the album as a whole. It leads directly into the 35-minute title track, and the album proper.

Opening with the continued cello and the addition of delicate vocals, the same sparse, intimate vibe continues, insinuating basic expectations for the rest of the album: from the sound and manner of recording, I was expecting an entire album of only strings and voice. Soon the cello drops away entirely, leaving just the vocals to be carefully looped and processed (in real time) into layers, any actual words become secondary to the melody created from the effects.

The returning cello cuts through the fragmented pieces of voice, resulting in a rich combination of natural and electronic sound that builds in density, resulting in a swirling mass of sound that takes a slightly darker turn, hovering ominously over droning low-end cello. The sound shifts in its closing, where the cello becomes less about texture and more about taut, rhythmic swipes that are layered upon themselves, resulting in a jarring, rapid motif that builds and builds into a suspenseful coda, ending what is mostly a reflective, contemplative piece on a tense, almost unsettling note.

As a completely live work, Leyf?u Ljósinu speaks volumes of Hildur Gu?nadóttir's ability as both a composer and performer. The building of sound from a delicate voice and cello to a heavy, swirling mass of sound and closing on a tense, rapid note works extremely well from a structural perspective, and the fact that it was all performed in real time with no overdubs or post-processing makes it all the more exceptional.

soundcolourvibration.com (USA):

Icelandic cellist and vocalist Hildur Gudnadottir has shocked me this year with the awe inspiring live performance album Leyfdu Ljosinu on the UK based imprint Touch. Recorded live with no audience at the Music Research Centre, University of Yorke in January of this year, the flowing essence of minimal presentation is astounding and as powerful as anything I have heard this year. Minimal in approach, Hildur Gudnadottir presents a four minute intro of eerie and slowly burning cello that sets the tone for the type of atmosphere that is to follow on Leyfdu Ljosinu. The following track contains the self titled piece and runs for almost forty minutes as one movement that shifts in various cycles that closes out the album. There is an underlining emotion and feeling that takes over the album, something that defines the albums purpose so well. It’s unbelievable how Hildur Gudnadottir achieves some of the layering that she does with electronics, cello and her vocals and it’s all very angelic and harmonious, never drifting outside of the realm of crystalline beauty. The climax of vocals, cello and electronics at the end is definitely worth the slowly building energy that this album paces at and displays a stunning performance of her cello capabilities with no post production involved.

Much of Leyfdu Ljosinu drifts and floats into different cascading cloths of color, folding inside of itself as each drifting moment cycles around to the other. The atmosphere feels cinematic and speaks for as much tension and restrain as it does muscular power and velocity. Leyfdu Ljosinu is really a remarkable testament to the importance of minimalism in ones music diet. As many albums strive to become large, this is the type of sound that feels large from the smallest of sources and the sound that isn’t being played by instruments becomes just as important as those present. In this world, the type of microphones utilized, a rooms acoustics and many more elements that lay unspoken in the albums final result become factors that give a much greater weight to the music than most contemporary records and is one that engineer Tony Myatt pulled off remarkably.

With vocals that sound like they are hardly surfacing through the depth of a blanketed forest in a lucid dream, intricately vibrant and softly placed loops and an overall musical imagination that paints thousands of pictures, Leyfdu Ljosinu truly becomes a magical and otherworldly vibration. [Erik Otis]

textura.org (USA):

Icelandic cellist Hildur Gudnadottir's Leyfdu ljosinu (Icelandic for ‘Allow the light') was recorded live in a single take at the Music Research Centre at the University of York in January 2012. No post-performance manipulations were applied, making the recording as accurate a rendering of the performance as possible. A solo recording in the truest sense, Leyfdu ljosinu finds the classically trained Gudnadottir (aka Lost In Hildurness) extending dramatically upon the sound-world presented in the work by using electronics to multiply her cello and voice. Loops are generated that then sustain themselves as base figures against which subsequent vocal and cello elements resound.

Opening with the cello alone and at its most natural, the brief “Prelude” lays the groundwork for the thirty-five-minute title track. Extended rests separate the bowed tones, almost as if to suggest the music's awakening, until Gudnadottir's soft voice appears to signal the start of the major section. An almost ghostly mood is created when her ethereal voice softly intones for minutes on end, the music's hypnotic character reinforced by the lulling, to-and-fro motion of its rhythms. Fourteen minutes into the second track, the cello starts to challenge the willowy vocals for dominance, the instrument swelling into rather cloud-like formations as it floods the aural space with its dramatic presence. Blocks of heaving strings surge dramatically, and a single cello eventually splits off from the whole, making it seem as if a single voice has risen to the surface of a turbulent, blurry mass, and grows ever more agitated as the end nears.

Gudnadottir makes full use of the title track's generous length to shape the music's arc with patience and deliberation. In fact, the growth in density occurs so gradually, it occurs almost imperceptibly, and it's only when one reaches the end of the recording that the overall shape of the material comes retroactively into clearer focus. Though it's admittedly more of a cello-based performance than cello-based composition, Leyfdu ljosinu presents a fascinating exercise in control in terms of execution and vision in terms of conceptual approach.

The Liminal (UK):

I’m given to thinking about space more and more at present – in a figurative and a literal sense. And call this hubris, but I can’t be the only one to have noticed this as a broader trend in cultural commentary. Everywhere I look I seem to see a new clamour for space – room – both in the forms under discussion, and something more indefinable, like a new, less frantic place to observe from. It feels almost like a reifying of the metaphoric critical claim for the high ground. It might also be characterised as a plea for stillness, to return to those near-sacred spaces of the past, those (probably illusory) zones which from this rocky vantage point look so full of pure experiential calm and purpose. And my instinct with all this is to say that it’s not just a continuation of the postmodern flattening of things, nor the concomitant ‘flattening’ of sound associated with MP3 culture, and not merely a ‘men of a certain age’ thing (which I’m tempted to call the End of Music syndrome) or a simple waning of affect – this feels new, or at least there’s enough different strands feeding into it for it to sound like a new cry.

That use of the word sacred is contentious (how could it be otherwise) but I’m not sure what other word fits, as tonally at least, this plea for space and the zone itself does have a whiff of the sacred. No other artform excites the easy need for reverence quite like music does (though you could argue it was there in the post-impressionists, particularly Rothko, and some would say too obscurely in Blanchot and the later post-structuralists), and ‘serious’, protective listeners and commentators, are increasingly demanding a shift/return to a kind of monkish devotion when it comes to listening to and commenting on music.

(There’s also, of course, the side issue of the reifying of this sacralising impulse in the continuing fetish for staging concerts in ostensibly sacred places and spaces. Acoustics aside, these concerts don’t perform any subversive function (as discussed by Tony Herrington in an acerbic Wire column), but instead seem to use these spaces in the hope of some referred numinosity or sublimity, a kind of lazy waft at grandiosity that fits with the aforementioned easy need for reverence.)

So what of it? Is there an answer to this cry? Is it merely a generational thing – ageing bodies doomed to chart the clicks and whirrs of metabolic degradation?

I wouldn’t want to characterise the entirety of its output, but there’s always been a trace of the sacred about a lot of the music released by Touch- and a genuine appreciation of space, both in and around the artists they’ve worked with and the methods they’ve used in recording and production, and subsumed in the sound itself. Much of the music makes demands of the listener – contemplation, immersion – and their appreciation of the tactile, fetish-like qualities of product also feeds into this. (By sacred I do mean in the most secular way possible, less in a religious aspect than in a devotional one, something close to Schopenhauer’s awed notion that ‘music floats to us as from a paradise quite familiar yet eternally remote… it reproduces all the emotions of our innermost being, but entirely without reality’. ) And if you were to select a modern figurehead for Touch’s loose ethos, you’d be hard pushed to find a better example than Hildur Gu?nadóttir.

Gu?nadóttir’s solo work to date is infused with this combination of the devotional and the spacious – you could even argue that in her work the inherent relationship between the two ideas/realms becomes increasingly obvious. The simplicity of what she does is at the heart of things - that unadorned nakedness of her cello, relying on its rough beauty of tone and timbre – but there is an ineffability to this simplicity that explanations only ever really brush up against. With Leyf?u Ljósinu it’s as if she’s reached the central secret of this simplicity, and there’s a real feeling of the inadequacy of language in attempting to identify it.

Take that title – Leyf?u Ljósinu. There’s an immediate sense that the phrase is untranslatable, that you’re only getting a hint of the meaning. It loosely translates as Allow The Light, which when you try and parse it, feels incomplete and kind of hovers between grammatical and lexical possibilities. It’s a command, but like Schopenhauer’s dictum, it sort of drifts in from another realm, and it’s also an impossible command, because one is unable to find a place of control – instead you have to wait, and let the natural order take its course. Which is as good an analogy for the experience of listening to Leyf?u Ljósinu as I can think of: it isn’t something you grasp and contain, rather you surrender yourself to it and (there needs to be a word for this) find a space of aural contemplation.

Leyf?u Ljósinu was recorded at the Music Research Centre, University of York in January of this year (2012). It was recorded live (without with an audience) and there has been no post-production tampering at all – all the sound processing (such as it is) took place during the 40 minutes of the performance. The ‘Prelude’ consists of little more than a two note cello figure, that rises out of the subterranean depths and sinks once more. This figure acts as a kind of undulating bedrock, the echo of which remains in and just out of earshot throughout the entirety of the main section. This main section begins with Hildur voicing a similar two note repeating figure which is then looped and very subtly layered until it becomes like a layer of vapour over the initial bedrock of the ‘Prelude’. Little else happens for the next few minutes until a thread-thin higher vibrating note is introduced – the introduction of which, seems to induce a sudden concentration on one’s own breathing patterns. The passage of air through the upper reaches of the body.

The resurgence of Gu?nadóttir’s cello, when it comes, is low and vast, almost leviathanic – a series of deep, humming notes that swarm beneath everything, and buoy up the already rising vocals. The cello gradually fills the field of the recording, somehow gathering space to itself and the thickening of the air around it is almost palpable. The mid-section becomes, then, a time-warping appreciation of the sonic potential of the cello. Somehow, putting time markers against specific phenomena seems pointless as in reality, what occurs is a kind of expansion: it’s almost as if you’re able to walk around inside the theatre (and sonic) space and feel the instrument as a tactile reality. You start to sense the individual wound fibres of the strings, packed together in their confined wire casings, the bristling hairs of the bow, the raised calluses on the player’s fingertips…

The gradual build to a climax is almost (only almost) anti-climactic in its way, as this contemplative spell is broken, but the enacted drama is a kind of necessary release from the madness of synaesthetic detail – a detail that feels dangerous to contemplate for too long, lest you never find a way out. What this section does need (and has in terms of density), is volume – furniture needs to shake, masonry to crumble…